Quality initiatives (QI) are often thought of as longitudinal projects that require large system lifts and complex multidisciplinary teams. These sorts of projects can be intimidating and time-consuming for attending physicians and learners to consider taking on. Participating in a project is not the only way to learn quality and patient safety, however.

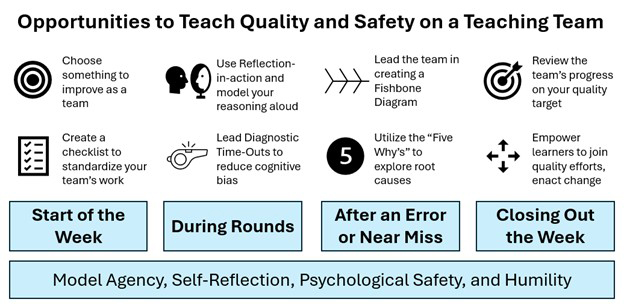

Clinician educators often forget that we are performing quality work in our heads every day, whether it be simple checklists, recognizing and assessing error, or even reconsidering our diagnostic choices. We people in the quality field can come off as constantly telling people things they should do, but a lot of the time, they are already doing these things; we just don’t recognize it as QI work. While the first step is recognition, the next step is how to teach this type of daily QI to learners. Here are our tips on how clinicians can take this internal-dialogue type of QI work out of our heads and into rounds.

Working Through Error Using a QI Lens

Inevitably, errors will happen on clinical service. Errors are an opportunity to perform and model good health care system stewardship with learners by performing a root cause analysis. Root cause analysis is a quality-improvement tool wherein an event is meticulously scrutinized to illuminate the system’s problems that led to harm. Who doesn’t go back and think about how or why it happened? By externalizing this practice to the learners on the team, you take something we already do and turn it into a QI teaching session.

This conversation is the easiest way to turn your internal dialogue into a teaching point. But, to take your QI teaching a step further, you can model the systematic application of tools for root cause analysis, including cause-and-effect diagrams and the “Five Whys.”

A cause-and-effect diagram ensures your root cause analysis is comprehensive by outlining a set of causal categories that the adverse event might fall into. The categories you pick are up to your discretion, but recommended categories for analyzing patient safety errors include care environment, personnel, policies and procedures, cognitive bias, equipment and supplies, and communication. You can lead your team in a chalk-talk-style teaching session where you evaluate an error or adverse event you encountered together by drawing a fishbone diagram. This will not only model good systems-improvement techniques but will also improve the end result of your root cause analysis by leveraging the collective intelligence of your teaching team.

A second tool to use when teaching QI through error analysis is the “Five Whys,” which is a heuristic construct based on the assumption that the most apparent cause of a patient-safety event is never the root cause, and that finding deeper and more systemic causes requires asking “Why?” five times. While it doesn’t always take exactly five inquiries to find a root cause, the spirit of the Five Whys is that one must ask “Why?” many times before underlying causes are found. To put this into practice, when readmitting a patient who has “bounced back,” use the Five Whys to encourage them to dig deeper into why the patient’s treatment plan failed.

Using QI Tools to Teach Clinical Reasoning and Avoid Cognitive Bias

Recognize the importance of turning self-reflection into quality education. We often think we are practicing the most current, evidence-based care, serving as pure conduits of scientific knowledge. But medicine is also an art. Quality work lives in this space, too, as diagnostic accuracy is a central QI goal. Two ways to bring this type of inner work to the bedside are clinical reasoning and cognitive bias.

Clinical reasoning skills can be fostered by encouraging learners to practice the QI tool, reflection-in-action. Reflection-in-action can be taught by modeling your own reasoning aloud. For instance, while on rounds, instead of simply asking learners to justify their thinking, try walking them through your approach to a complex diagnosis or management plan. Additionally, if a learner is struggling to reach a diagnosis, invite them to verbalize their diagnostic reasoning. This can help them identify where they may be getting stuck. Structured frameworks like illness scripts or SNAPPS (summarize, narrow, analyze, probe, plan, select) can be especially helpful in guiding these discussions.

Even when clinical reasoning is sound, common cognitive biases can impede our learners’ successes in both diagnostic stewardship and clinical reasoning. Several strategies can help reduce the influence of cognitive bias while on rounds, including a diagnostic timeout, which is particularly useful when there is diagnostic uncertainty within the team or when a team member appears anchored on a diagnosis that doesn’t fully fit the clinical picture. To put this into practice, pause rounds for the timeout and ask everyone to offer a differential diagnosis while the rest of the team offers supporting and refuting evidence. Some great times to use this are altered mental status not improving or a persistent leukocytosis.

Rethinking the Standard Work a Teaching Team is Doing as QI Education

Even if we are achieving accurate diagnoses, the work we do on rounds with our team is extremely complicated work where data, observation, medical decision making, and communication interplay, and care of our patients can suffer if a team isn’t utilizing the system well. When your team isn’t working right, this can be a great time to identify functions that could be improved.

At the start of a week of service, ask your team to identify one process they can improve upon. Good targets include medication reconciliation, catheter and line assessment, telemetry discontinuation, or contacting families. Decide with your team how you’ll measure and monitor your progress. At the conclusion of the week, review the experience and share any measurements you have. This mini exercise is a QI project in and of itself and is a great way to galvanize your team around a process.

Another aspect of internal work we all do as hospitalists is checklists. Checklists are a central tool to standardize processes and reduce unintended omissions. Where this topic can be fun and engaging with your team is in identifying processes that do not have checklists that might benefit from them. Some faculty in our hospital medicine group recognized the likelihood for error within the discharge process as one on which we could improve and designed our own discharge checklist. To facilitate its use, we adopted the acronym DDEMAP—Destination (where is patient going: home, skilled nursing facility, long-term acute care facility), Diagnoses (encountered during hospital stay), Equipment (any durable medical equipment patient should be discharged with), Medications (listing out all the home medications as well as any changes), Appointments (all follow-up appointments), and Pending (any tests still pending at discharge that will require follow-up). Use of the tool almost invariably results in some change or clarification, and when we studied it, a change occurred in 79% of timeouts, half of which were medication changes.

Your health system likely has a process (or five) that could use some shoring up. Also, consider brainstorming a novel checklist with your team. Try it out with your team and see if it sticks!

A lot of what we are promoting is good teaching practices, and teaching QI at the bedside is not far off from just being a good teacher. It’s not surprising, then, that in order to put any of these tools into practice, a baseline of a safe learning climate is required. Tools aren’t everything, though. More important than using any tool is modeling humility, openness, and self-reflection in the face of an adverse event.

By using these tools in a safe setting for learners, academic hospitalists can make QI applicable to our daily work and more easily consumable for learners. Thinking about QI outside of the usual lecture setting, which most of us experienced in our own education, is unique. Further, these activities can help learners understand that the system is here to help us, empower them by demonstrating participatory agency in the system, and even lead to those intimidating, bigger projects and quality work. As an educator, taking your QI work to rounds will leave an impression on your learners. We hope this work will help people you’ll never meet and positively impact systems you’ll never work in.

Dr. Shaw

Dr. Pizanis

Dr. Porter

Dr. Zimmerberg-Helms

Dr. Shaw is an associate professor in the division of hospital medicine’s department of internal medicine, an associate program director of the internal medicine residency, an assistant clerkship director of the internal medicine clerkship, and the vice section chief of education for hospital medicine at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, N.M. Dr. Pizanis is an associate professor in the division of hospital medicine’s department of internal medicine, co-director of the UNM hospitalist training track, and co-directs the UNM quality and safety scholars program at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque, N.M. He is also an editorial board member for The Hospitalist. Dr. Porter is a hospitalist and assistant professor in medicine-hospital medicine at the University of Colorado in Aurora, Colo. Dr. Zimmerberg-Helms is a hospitalist, faculty member, and associate vice chair of quality at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, N.M.