The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends treating a provoked VTE for three months.19 According to the same guidelines, an unprovoked VTE should be treated for a minimum of three months, and lifelong anticoagulation should be considered.19

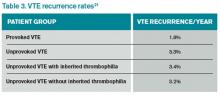

Overall, the rate of recurrence after a first VTE is considerable after completion of anticoagulation, especially for an unprovoked thrombotic event. Studies show a 7%-15% recurrence rate during the two years following the index VTE (see Table 3).17,20,21 Currently, no data suggest that a hereditary thrombophilia substantially changes this baseline high recurrent risk. ACCP recommendations state that the presence of hereditary thrombophilia should not be used as a major factor to guide duration of anticoagulation.19

Back to the Case

Our patient presented with an unprovoked VTE. She should be started on anticoagulation therapy with low molecular weight heparin and transitioned to oral anticoagulation.

Her highest risk for VTE recurrence is the unprovoked VTE itself, regardless of an underlying thrombophilia. Since the presence of an inherited thrombophilia will not change duration or intensity of management, our patient should not be tested.

There are no prospective trials showing improved outcomes from aggressive workup for occult malignancy. Given this information, an extensive workup for occult malignancy should not be undertaken; however, this patient has an idiopathic VTE and should undergo a complete history, physical examination, and basic lab work, with attention to common areas of malignancy. Any abnormalities uncovered on this initial workup should be investigated more aggressively. Screening with mammography and Pap smear should be arranged in outpatient follow-up and communicated to the primary care physician, because she is not up to date with these age-appropriate screening tests.

Based on new evidence, a low-dose chest CT would be a consideration if she had a smoking history of at least 30 pack-years.22 Her microcytic anemia uncovered on routine lab work should be investigated further for a possible underlying gastrointestinal malignancy.

Bottom Line

An initial diagnosis of unprovoked VTE remains the strongest risk factor for recurrent thromboembolic events. The presence of an inherited thrombophilia does not significantly alter management. Aggressive workup for occult malignancy has not prospectively improved outcomes, but age-appropriate malignancy screening should be recommended.

Drs. Czernik and Anderson are hospitalists and instructors of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver (UCD). Dr. Wolfe is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at UCD. Dr. Cumbler is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at UCD.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Venous thromboembolism in adult hospitalizations—United States, 2007–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(22);401-404.

- Baglin T, Gray E, Greaves M, et al. Clinical guidelines for testing for heritable thrombophilia. Br J Haematol. 2010;149(2):209-220.

- Heit, JA, O’Fallon WM, Petterson TM, et al. Relative impact of risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(11):1245-1248.

- Iodice S, Gandini S, Löhr M, Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P. Venous thromboembolic events and organ-specific occult cancers: a review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(5):781-788.

- Coppens M, Reijnders JH, Middeldorp S, Doggen CJ, Rosendaal FR. Testing for inherited thrombophilia does not reduce the recurrence of venous thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(9):1474-1477.

- Coppens M, van Mourik JA, Eckmann CM, Büller HR, Middeldorp S. Current practise of testing for inherited thrombophilia. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(9):1979-1981.

- Carrier M, Le Gal G, Wells PS, Fergusson D, Ramsay T, Rodger MA. Systematic review: the Trousseau syndrome revisited: should we screen extensively for cancer in patients with venous thromboembolism? Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(5):323-333.

- Cronin-Fenton DP, Søndergaard F, Pedersen LA, et al. Hospitalisation for venous thromboembolism in cancer patients and the general population: a population-based cohort study in Denmark, 1997-2006. Br J Cancer. 2010;103(7):947-953.

- Chew HK, Wun T, Harvey D, Zhou H, White RH. Incidence of venous thromboembolism and its effect on survival among patients with common cancers. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(4):458-464.

- Lee JL, Lee JH, Kim MK, et al. A case of bone marrow necrosis with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura as a manifestation of occult colon cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004;34(8):476-480.

- Sack GH Jr, Levin J, Bell WR. Trousseau’s syndrome and other manifestations of chronic disseminated coagulopathy in patients with neoplasms: clinical, pathophysiologic, and therapeutic features. Medicine (Baltimore). 1977;56(1):1-37.

- Prins MH, Hettiarachchi RJ, Lensing AW, Hirsh J. Newly diagnosed malignancy in patients with venous thromboembolism. Search or wait and see? Thromb Haemost. 1997;78(1):121-125.

- Cornuz J, Pearson SD, Creager MA, Cook EF, Goldman L. Importance of findings on the initial evaluation for cancer in patients with symptomatic idiopathic deep venous thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125(10):785-793.

- Lee AY, Levine MN, Baker RI, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin versus a coumarin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(2):146-153.

- Dalen JE. Should patients with venous thromboembolism be screened for thrombophilia? Am J Med. 2008;121(6):458-463.

- Khamashta MA, Cuadrado MJ, Mujic F, Taub NA, Hunt BJ, Hughes GR. The management of thrombosis in the antiphospholipid-antibody syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:993-997.

- Ridker PM, Goldhaber SZ, Danielson E, et al. Long-term, low-intensity warfarin therapy for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(15):1425-1434.

- Hron G, Eichinger S, Weltermann A, et al. Family history for venous thromboembolism and the risk for recurrence. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):50-53.

- Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e419S-e494S.

- Douketis, James, Tosetto A, Marcucci M, et al. Risk of recurrence after venous thromboembolism in men and women: patient level meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:d813.

- Christiansen SC, Cannegieter SC, Koster T, Vandenbroucke JP, Rosendaal FR. Thrombophilia, clinical factors, and recurrent venous thrombotic events. JAMA. 2005;293(19):2352-2361.

- American Cancer Society Guidelines for the Early Detection of Cancer. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/healthy/findcancerearly/cancerscreeningguidelines/american-cancer-society-guidelines-for-the-early-detection-of-cancer. Accessed November 15, 2014.