Case

A 56-year-old woman with hypertension and diabetes presents to the hospital with acute onset of painful swelling in her right calf. She has had no recent surgeries, trauma, or travel, and takes lisinopril and metformin. An ultrasound of her right lower extremity demonstrates a venous thromboembolism (VTE). The patient’s last mammogram was three years ago, and she’s never undergone a screening colonoscopy. On lab workup, she is noted to have a microcytic anemia.

Should this patient be screened for an underlying hypercoagulable state or malignancy?

Background

An estimated 550,000 hospitalized adults are diagnosed with VTE each year.1 VTE can occur in the absence of known precipitants (unprovoked) or can be temporally associated with a known major risk factor (provoked). This practical division has implications for both treatment duration and risk of recurrence. A VTE is considered provoked if it occurs in the setting of surgery, leg trauma, fracture, pregnancy within the previous three months, estrogen therapy, immobility from an acute illness for more than one week, travel lasting more than six hours, or active malignancy.2 If none of these provoking factors is present, the VTE is considered unprovoked.2

Nearly 20% of first-time VTE events can be attributed to malignancy.3 Additionally, patients presenting with an unprovoked VTE possess a higher risk of being diagnosed with a cancer, raising the question of whether unprovoked VTEs should compel aggressive malignancy screening.4

Before the discovery of antithrombin deficiency in 1965, most unprovoked VTE events remained unexplained. Since then, numerous inherited coagulation abnormalities have been identified. It is now estimated that coagulation abnormalities can be found in up to half of patients with unprovoked thrombi.5

The increase in availability of molecular and genetic assays for hypercoagulability has been accompanied by a dramatic rise in the rate of testing for these disorders.6 Despite increased testing available for inherited thrombophilias, disagreement exists over the utility of this workup.6

Review of the Data

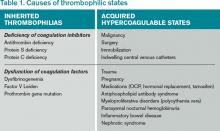

Hypercoagulability leading to venous thrombosis can be broadly divided into two groups: acquired and hereditary (see Table 1). First, let’s examine acquired hypercoagulable states.

Malignancy: Armand Trousseau first suggested an association between thrombotic events and malignancy in 1865. Malignancy causes a hypercoagulable state; additionally, tumors can cause thromboemboli by other mechanisms, such as vascular invasion or external compression of vasculature.7

Multiple studies demonstrate that malignancy increases the chance of developing a VTE. A Danish cohort study of nearly 60,000 cancer patients compared with over 280,000 controls over nine years offered twice the incidence of VTE in patients with cancer.8 Other studies reveal that VTE rates peak in the first year after a cancer diagnosis; moreover, VTE events are associated with more advanced disease and worse prognosis.9 Approximately 11% of cancer patients will develop a clinically evident VTE during the course of their disease.10,11

The majority of cancers associated with VTE events are clinically evident; however, some patients with thrombi have an occult malignancy. During the two years following an unprovoked VTE, the rate of discovering a previously undiagnosed malignancy was three times higher when compared with provoked VTE.6