Heinous Crimes

By the time a mortician in the northeast British town of Hyde, Greater Manchester, United Kingdom, noticed Dr. Harold Shipman’s patients were dying at an exorbitant rate, the doctor had probably killed close to 300 of them, according to Kenneth V. Iserson, MD, MBA, professor of emergency medicine at the University of Arizona College of Medicine and author of “Demon Doctors: Physicians as Serial Killers.”

Shipman, labeled ‘‘the most prolific serial killer in the history of the United Kingdom—and probably the world,’’ was officially convicted of killing 15 patients in 2000 and sentenced to 15 consecutive life sentences.1 In January 2004 he was found hanged in his prison cell.

Sometimes referred to as caregiver-associated serial killings, these incidents generate profound shock in the healthcare community. As repellent and relatively rare as this behavior is, and as controversial as the topic is, neither individuals nor institutions can afford to disassociate themselves from the subject. Hospitalists should not hide from this issue and should not feel they will be accused of “treason” if they educate themselves and bring suspicious behavior to the awareness of superiors, says Beatrice Crofts Yorker, JD, RN, MS, FAAN, dean of the College of Health and Human Services at California State University, Los Angeles. On the contrary, she says, “first, do no harm” also entails ensuring everyone else around you follows the same ethic.

Dr. Yorker, who has been studying this phenomenon since 1986, published the first examination of cases of serial murder by nurses in the American Journal of Nursing (AJN) in 1988. “It is a serious problem that has been under-recognized, and it is the right thing to blow the whistle when adverse patient incidents are associated with the presence of a specific healthcare provider,” says Dr. Yorker. “In fact, most of the cases came to the attention of authorities because a nurse blew the whistle. The sad thing is that some of the nurses were disciplined for their protective actions; however, they were ultimately vindicated.”

A veteran of the phenomenon urges continued vigilance. “As a general caveat, there needs to be a higher index of suspicion for these incidents,” says Kenneth W. Kizer, MD, MPH, the former head of the veterans healthcare system who had to deal with three incidents of serial murder at Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals in the 1990s. “These incidents are grossly underreported.”

Incidence and Cause of Death

Drs. Kizer and Yorker were two of the investigators who reviewed epidemiologic studies, toxicology evidence, and court transcripts for data on healthcare professionals prosecuted between 1970 and 2006.

“Dr. Robert Forrest, who was a forensic toxicologist getting a law degree and wrote his dissertation on the topic of serial murder by healthcare providers, contacted me after the AJN article came out,” says Dr. Yorker. Dr. Forrest has been the testifying expert in most of the U.K. cases. “After the Charles Cullen case hit the news, The New York Times and Modern Healthcare contacted me regarding my study in AJN and the Journal of Nursing Law. That is how Ken Kizer and Paula Lampe found me.” (Cullen, a registered nurse, received 11 consecutive life sentences in 2006 after pleading guilty to administering lethal doses of medication to more than 40 patients in New Jersey and Pennsylvania.)

Lampe, an author, had been studying cases in Europe. “Because both Robert and Paula provided additional data on some cases, they were co-authors—as was Ken—who provided data on the VA cases and an important public policy perspective,” says Dr. Yorker.

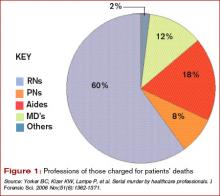

The search showed 90 criminal prosecutions of healthcare providers who met the criteria of serial murder of patients. Of those, 54 have been convicted—45 for serial murder, four for attempted murder, and five on lesser charges. Since the publication of their study, one more of the accused has received a sentence of life in prison, another has been convicted and sentenced to 20 years, one committed suicide in prison, and two additional nurses in Germany and the Czech Republic have been arrested and confessed to serial murder of patients. In addition, Dr. Yorker is continuing to follow two large-scale murder-for-profit prosecutions. There are four defendants in each case. Further, three individuals have been found liable for wrongful death in the amounts of $27 million, $8 million, and $450,000 in damages.