How to manage submassive pulmonary embolism

The case

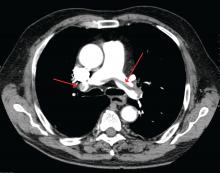

A 49-year-old morbidly obese woman presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath and abdominal distention. On presentation, her blood pressure was 100/60 mm Hg with a heart rate of 110, respiratory rate of 24, and a pulse oximetric saturation (SpO2) of 86% on room air. Troponin T was elevated at 0.3 ng/mL. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with intravenous contrast showed saddle pulmonary embolism (PE) with dilated right ventricle (RV). CT abdomen/pelvis revealed a very large uterine mass with diffuse lymphadenopathy.

Heparin infusion was started promptly. Echocardiogram demonstrated RV strain. Findings on duplex ultrasound of the lower extremities were consistent with acute deep vein thromboses (DVT) involving the left common femoral vein and the right popliteal vein. Biopsy of a supraclavicular lymph node showed high grade undifferentiated carcinoma most likely of uterine origin.

Clinical questions

What, if any, therapeutic options should be considered beyond standard systemic anticoagulation? Is there a role for:

1. Systemic thrombolysis?

2. Catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT)?

3. Inferior vena cava (IVC) filter placement?

What is the appropriate management of “submassive” PE?

In the case of massive PE, where the thrombus is located in the central pulmonary vasculature and associated with hypotension due to impaired cardiac output, systemic thrombolysis, embolectomy, and CDT are indicated as potentially life-saving measures. However, the evidence is less clear when the PE is large and has led to RV strain, but without overt hemodynamic instability. This is commonly known as an intermediate risk or “submassive” PE. Submassive PE based on American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines is:1

An acute PE without systemic hypotension (systolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg) but with either RV dysfunction or myocardial necrosis. RV dysfunction is defined by the presence of at least one of these following:

• RV dilation (apical 4-chamber RV diameter divided by LV diameter greater than 0.9) or RV systolic dysfunction on echocardiography;

• RV dilation on CT, elevation of BNP (greater than 90 pg/mL), elevation of N-terminal pro-BNP (greater than 500 pg/mL);

• Electrocardiographic changes (new complete or incomplete right bundle branch block, anteroseptal ST elevation or depression, or anteroseptal T-wave inversion).

Myocardial necrosis is defined as elevated troponin I (greater than 0.4 ng/mL) or elevated troponin T (greater than 0.1 ng/mL).

Why is submassive PE of clinical significance?

In 1999, analysis of the International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry (ICOPER) revealed that RV dysfunction in PE patients was associated with a near doubling of the 3-month mortality risk (hazard ratio 2.0, 1.3-2.9).2 Given this increased risk, one could draw the logical conclusion that we need to treat submassive PE more aggressively than PE without RV strain. But will this necessarily result in a better outcome for the patient given the 3% risk of intracranial hemorrhage associated with thrombolytic therapy?

In the clinical scenario above, the patient did meet the definition of submassive PE. While the patient did not experience systemic hypotension, she did have RV dilation on CT, RV systolic dysfunction on echo as well as an elevated Troponin T level. In addition to starting anticoagulant therapy, what more should be done to increase her probability of a good outcome?

The AHA recommends that systemic thrombolysis and CDT be considered for patients with acute submassive PE if they have clinical evidence of adverse prognosis, including worsening respiratory failure, severe RV dysfunction, or major myocardial necrosis and low risk of bleeding complications (Class IIB; Level of Evidence C).1

The 2016 American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) guidelines update3 recommends systemically administered thrombolytic therapy over no therapy in selected patients with acute PE who deteriorate after starting anticoagulant therapy but have yet to develop hypotension and who have a low bleeding risk (Grade 2C recommendation).

Systemic thrombolysis

Systemic thrombolysis is administered as an intravenous thrombolytic infusion delivered over a period of time. The Food and Drug Administration–approved thrombolytic drugs currently include tissue plasminogen activator (tPA)/alteplase, streptokinase and urokinase.

In the 2002 randomized, double-blind Pulmonary Embolism-3 Trial,4 Konstantinides and colleagues compared heparin plus tPA versus heparin plus placebo in 256 patients with submassive PE. The primary clinical endpoint of death or in-hospital escalation of care was 11.0 % in the tPA group versus 24.6% in the placebo group (P = .006); the difference was driven largely by the escalation of care, defined as use of vasopressors, rescue thrombolysis, mechanical ventilation, cardiac arrest, and requirement of surgical embolectomy. Perhaps surprisingly, there were no cases of hemorrhagic stroke in either of these groups. The trial demonstrated that systemic thrombolysis in submassive PE was associated with a lower risk of death and treatment escalation.

Efficacy of low dose thrombolysis was studied in MOPETT 2013,5 a single-center, prospective, randomized, open label study, in which 126 participants found to have submassive PE based on symptoms and CT angiographic or ventilation/perfusion scan data received either 50 mg tPA plus heparin or heparin anticoagulation alone. The composite endpoint of pulmonary hypertension and recurrent PE at 28 months was 16% in the tPA group compared to 63% in the control group (P less than .001). Systemic thrombolysis was associated with lower risk of pulmonary hypertension and recurrent PE, although no mortality benefit was seen in this small study.

In the randomized, double-blind PEITHO trial (n = 1,006) of 20146 comparing tenecteplase plus heparin versus heparin in the submassive PE patients, the primary outcomes of death and hemodynamic decompensation occurred in 2.6% of the tenecteplase group, compared to 5.6% in the placebo group (P = .02). Thrombolytic therapy was associated with 2% rate of hemorrhagic stroke, whereas hemorrhagic stroke in the placebo group was 0.2% (P = .03). In this case, systemic thrombolysis was associated with a 3% lower risk of death and hemodynamic instability, but also a 1.8% increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke.