Case

A 70-year-old woman was brought to the ED by ambulance with slurred speech after a fall. She arrived in the ED three hours and 29 minutes after the last time she was known to be normal. On initial examination, she had a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of 13, with a left facial droop, left hemiplegia, and right gaze deviation. Her acute noncontrast head computed tomography (CT), CT angiogram, and CT perfusion scans are shown in Figure 1.

How should this patient’s acute stroke be managed at this time?

Overview

Pathophysiology/Epidemiology: Stroke is the fourth most common cause of death in the United States and the main cause of disability, resulting in substantial healthcare expenditures.1 Ischemic stroke accounts for about 85% of all stroke cases and has several subtypes. The most common causes of ischemic stroke are small vessel thrombosis, large vessel thromboembolism, and cardioembolism. Both small vessel thrombosis and large vessel thromboembolism often are related to typical atherosclerotic risk factors, and cardioembolism is most often related to atrial fibrillation/flutter.

Minimizing death and disability from stroke is dependent on prevention measures, as well as early response to the onset of symptoms. The typical patient loses 1.9 million neurons for every minute a stroke is untreated—hence the popular adage “Time is Brain.”2 Although the appropriate management and time window of stroke treatment have been somewhat controversial, the acuity of treatment is now undisputed. Intravenous thrombolysis with tPA, also known as alteplase, has been an FDA-approved treatment for stroke since 1996, yet, as of 2006, only 2.4% of patients hospitalized for ischemic stroke were treated with IV tPA.3

The etiology of stroke, in most cases, does not change management in the hyperacute period, when thrombolysis is appropriate regardless of etiology.

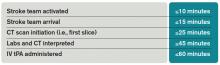

Timely evaluation: Although recognition of stroke symptoms by the public and pre-hospital management is a barrier in the treatment of acute stroke, this article will focus on appropriate ED and in-hospital treatment of stroke. Given the urgent need for management of acute ischemic stroke, it is critical that hospitals have an efficient process for identifying possible strokes and beginning treatment early. In order to accomplish these objectives, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) has established goals for time frames of evaluation and management of patients with stroke in the ED (see Table 1).4

The role of the hospitalist: Hospitalists can play critical roles both as part of a primary stroke team and in identifying missed strokes. Some acute stroke teams have included hospitalists due to their ability to help with medical management, identify mimics, and assess medical contraindications to thrombolytic therapy. In addition, hospitalists may be the first to recognize a stroke in the ED when evaluating a patient with symptoms confused with a medical condition, or when a stroke occurs in an inpatient. In both of these situations, as first responders, hospitalists have knowledge of stroke evaluation and treatment that is crucial in beginning the evaluation and triggering a stroke alert.

Diagnostic tools: The initial evaluation of a patient with a possible stroke includes a brief but thorough history of current symptoms, as well as past medical and medication histories. The most critical piece of information to obtain from patients, family members, or bystanders is the time of symptom onset, or the time the patient was last known normal, so that the options for treatment can be evaluated early.