The Case

A 50-year-old man with no known medical history presents with two months of increasing abdominal distension. Exam is notable for scleral icterus, telangiectasias on the upper chest, abdominal distention with a positive fluid wave, and bilateral pitting lower-extremity edema. An abdominal ultrasound shows large ascites and a nodular liver consistent with cirrhosis. How should this patient with newly diagnosed cirrhosis be evaluated and managed?

Background

Cirrhosis is a leading cause of death among people ages 25–64 and associated with a mortality rate of 11.5 per 100,000 people.1 In 2010, 101,000 people were discharged from the hospital with chronic liver disease and cirrhosis as the first-listed diagnosis.2 Given the myriad etiologies and the asymptomatic nature of many of these conditions, hospitalists frequently encounter patients presenting with advanced disease.

Evaluation

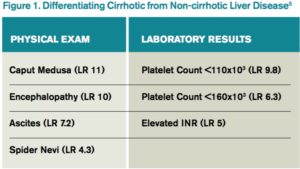

The first step in evaluation is to differentiate cirrhotic from non-cirrhotic liver disease. Figure 1 lists physical exam and laboratory findings helpful in staging liver disease. Imaging (ultrasound, computerized tomography [CT], or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) is not diagnostic in isolation but can be used to confirm cirrhosis in the presence of associated findings on exam and laboratory studies.

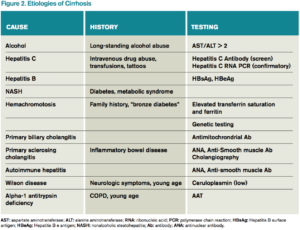

The gold standard for diagnosis is liver biopsy, although this is now usually reserved for atypical cases or where the etiology of cirrhosis is unclear. Alcohol and viral hepatitis (B and C) are the most common causes of chronic liver disease, with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) increasing in prevalence. Other less common etiologies and characteristic test findings are listed in Figure 2.

Recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that adults born between 1945 and 1965 receive one-time testing for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, regardless of other risk factors, given the higher prevalence in this birth cohort and the introduction of newer oral treatments that achieve sustained virologic response.3

Management

The three classic complications of cirrhosis that will typically prompt inpatient admission are volume overload/ascites, gastrointestinal variceal bleeding, and hepatic encephalopathy.

Volume overload/ascites. Ascites is the most common major complication of cirrhosis, with roughly 50% of patients with asymptomatic cirrhosis developing ascites within 10 years.4 Ascites development portends a poor prognosis, with a mortality of 15% within one year and 44% within five years of diagnosis.4 Patients presenting with new-onset ascites should have a diagnostic paracentesis performed to determine the etiology and evaluate for infection.

Ascitic fluid should be sent for an albumin level and a cell count with differential. A serum-ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) of greater than or equal to 1.1 g/dL is consistent with portal hypertension and cirrhosis, while values less than 1.1 g/dL suggest a non-cirrhotic cause, such as infection or malignancy. Due to the high prevalence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) in hospitalized patients, fluid should also be immediately inoculated in aerobic and anaerobic culture bottles at the bedside, as this has been shown to improve the yield compared to inoculation of culture bottles in the laboratory. Other testing (such as cytology for the evaluation of malignancy) should only be performed if there is significant concern for a particular disease since the vast majority of cases are secondary to uncomplicated cirrhosis.4

In patients with a large amount of ascites and related symptoms (eg, abdominal pain, shortness of breath), therapeutic paracentesis should be performed. Although there is controversy over the need for routine albumin administration, guidelines currently recommend the infusion of 6–8 g of albumin per liter of ascites removed for paracentesis volumes of greater than 4–5 liters.4

No data support the routine administration of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) or platelets prior to paracentesis. Although significant complications of paracentesis (including bowel perforation and hemorrhage) may occur, these are exceedingly rare. Ultrasonography can be used to decrease risks and identify suitable pockets of fluid to tap, even when fluid is not obvious on physical exam alone.5