A 75-year-old female nursing-home resident with mild cognitive impairment is admitted to the hospital for two days of confusion, agitation, and weakness. She denies any genitourinary symptoms, abdominal pain, or fevers. Vital signs show a temperature of 37.7°C (99.8°F), heart rate of 90 beats per minute, BP 100/70 mmHg, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, and O2 saturation 95% on room air. The workup included a white blood cell count of 11,000/μL and a clean-catch urinalysis with positive nitrite, 2+ leukocyte esterase, 18 white blood cells (WBC) per high-power field (HPF), and five squamous cells. Should antibiotics be initiated in this patient?

Brief overview

Urinalysis is the oldest laboratory test ever performed. It is a fast, easy, low-cost test for a variety of clinical applications, from screening for proteinuria or pyuria to monitoring hematuria. Pyuria, usually defined as >5 to 10 white blood cells per HPF, has traditionally been used as a screening test for bacteriuria. Leukocyte esterase (LE), an enzyme found in most neutrophils, is an indirect test for pyuria. Nitrite testing identifies bacteria in the urine that convert nitrates to nitrites, such as the gram-negatives Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Proteus mirabilis.

Hospitalists use urinalysis to determine the likelihood of bacteriuria, often leading to a diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) and antibiotic treatment. UTIs are one of the most common infections in older adults, defined by bacteriuria (>105 colony-forming units [CFU]/mL) with symptoms attributable to the urinary tract. However, older adults commonly have bacteriuria without symptoms localizing to the urinary tract, known as ASB or asymptomatic bacteriuria. ASB only requires treatment if the patient is pregnant or has a planned urologic procedure, per guidelines of multiple societies, including the Infectious Diseases Society of America; American Geriatric Society; American Urological Association; Canadian Urological Association; Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine, and Urogenital Reconstruction; and European Society of Urology. Despite these guidelines, antibiotic treatment based on initial urinalysis in the asymptomatic geriatric population remains commonplace,1 as does the notion that such treatment will reduce the duration or intensity of a patient’s nonspecific symptoms such as delirium.2

Overview of the data

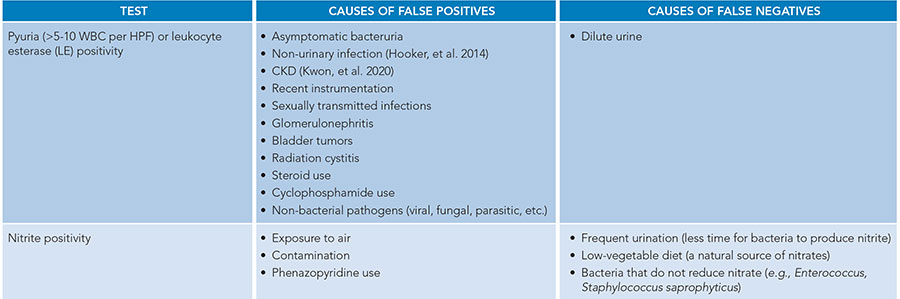

Like all tests, urinalysis is susceptible to false-positive and false-negative results (Table 1).3 For example, pyuria can be from sexually transmitted infections, medications, radiation, and even non-urinary infections. Similarly, nitrites can turn positive from medications or even exposure to air. Approximately 90% of urinalyses are not performed via the mid-stream clean catch method. However, evidence that this technique decreases contamination is uncertain.4

Retrospective studies have found that the degree of pyuria positively correlates with the odds of receiving antibiotics.1 However, prospective and retrospective studies of emergency department patients and inpatients have found the positive likelihood ratio of pyuria, nitrites, or LE is very low (1.1 to 1.8) in predicting bacteriuria.5 A study utilizing flow cytometry to accurately quantify pyuria revealed that the currently used pyuria cutoff with microscopy is 100% sensitive but only 36% specific in geriatric women with UTI or ASB.3 Assuming a linear relationship between pyuria on microscopy and flow cytometry, cutoffs of approximately 57 WBC per HPF would be more accurate in this population (sensitivity 84%, specificity 88%) compared to the cut-off of 10 WBC per HPF used by most clinicians.

Table 1

Despite society guidelines and the aforementioned shortcomings of urinalyses, pyuria and/or nitrites on urinalysis are often equated to UTI or “infected urine” in clinical practice, independent of the clinical context. This presumption leads to increased urine culture collection and antibiotic administration. However, all screening tests should be interpreted in the clinical context. For example, an elevated high-sensitivity troponin in a patient without a clinical correlate of acute coronary syndrome does not prompt intervention (heparin infusions, echocardiograms, and left heart catheterization). Instead, providers put the troponin values within the clinical context of the patient and then weigh the probability that such positive troponins represent a coronary event. Similarly, urinalysis showing pyuria or LE should not prompt urine culture and antibiotics but instead should prompt clinicians to consider such findings in the context of the patient’s symptoms, age, comorbidities, and other diagnoses on the differential.

Longstanding clinical teaching purports a link between neurocognitive symptoms and UTIs (the cystocerebral axis) in geriatric patients. Clinical teaching of common infections, such as dental infections, osteomyelitis, and cellulitis, does not include an association with neurocognitive symptoms. Decades of evidence suggest that UTI is no exception. In 1996, a double-blind placebo-controlled trial of geriatric post-acute care patients with bacteriuria found no difference in objective measures of behavior between norfloxacin-treated and placebo-treated patients.6 A decade later, Dasgupta et al. conducted a prospective cohort study of hospitalized adults with or without delirium and found that treating ASB was not associated with benefits to function or objectively assessed delirium.7 A single-center retrospective chart review of geriatric inpatients (more than 50% with dementia, more than 50% admitted from a facility, more than 25% with diabetes mellitus, and 15% with UTI in the past six months) with objective evidence of delirium and either positive LE or nitrites found no difference in delirium at one week independent of antibiotic use.8 This is supported by a recent systematic review, which determined that treating ASB did not improve delirium.9

While these studies of neurocognitive symptoms, UTI, and ASB are helpful, they have considerable heterogeneity, ranging from the exclusion of patients unable to express their symptoms to the use of different definitions of UTI. Improved methodology, such as a randomized clinical trial, is needed; one such trial is currently enrolling patients.10 Currently, the Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines on ASB note correctly that there is no evidence to support associations between ASB and falls, confusion, or non-localizing symptoms. These guidelines were highlighted in the Journal of Hospital Medicine’s “Things We Do for No Reason,” which covered the folly of screening older patients with delirium using urinalysis and culture.11 Instead, the authors recommend obtaining the history from a reliable informant, performing a thorough physical and neurologic examination, and evaluating for metabolic and electrolyte derangements. Current expert recommendations include taking these first steps in the first 24 to 48 hours as opposed to sending urine studies for stable patients without clear genitourinary symptoms. For patients with sepsis, hemodynamic instability, and or symptoms of a urinary tract infection, it is appropriate to obtain a urinalysis with urine culture and administer empiric antibiotics.

While these studies of neurocognitive symptoms, UTI, and ASB are helpful, they have considerable heterogeneity, ranging from the exclusion of patients unable to express their symptoms to the use of different definitions of UTI. Improved methodology, such as a randomized clinical trial, is needed; one such trial is currently enrolling patients.10 Currently, the Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines on ASB note correctly that there is no evidence to support associations between ASB and falls, confusion, or non-localizing symptoms. These guidelines were highlighted in the Journal of Hospital Medicine’s “Things We Do for No Reason,” which covered the folly of screening older patients with delirium using urinalysis and culture.11 Instead, the authors recommend obtaining the history from a reliable informant, performing a thorough physical and neurologic examination, and evaluating for metabolic and electrolyte derangements. Current expert recommendations include taking these first steps in the first 24 to 48 hours as opposed to sending urine studies for stable patients without clear genitourinary symptoms. For patients with sepsis, hemodynamic instability, and or symptoms of a urinary tract infection, it is appropriate to obtain a urinalysis with urine culture and administer empiric antibiotics.

Delirium is not the only unchanged outcome reviewed in the treatment of ASB. A retrospective chart review found that patients with sterile pyuria on pre-operative urinalyses who were treated with antibiotics had no improvement in postoperative outcomes.1 More importantly, these patients had higher rates of Clostridium difficile infection postoperatively (adjusted odds ratio, 2.4).1

Application to the case

Our patient is at high risk for pyuria and bacteriuria but lacks symptoms of a UTI. Given her age and the presence of squamous cells, her pyuria has a low positive likelihood ratio for bacteriuria. Her positive nitrites could be from bacteriuria, but their presence is not a surrogate for the genitourinary symptoms necessary to diagnose UTI. Considering other causes of her delirium and weakness should start with a discussion with her caregivers to determine her baseline level of cognition and function, review of any recent psychosocial changes and medications, and thorough neurologic exam in addition to a review and workup for common causes of delirium and weakness such as metabolic derangements and electrolyte disturbances.

Bottom line

Hospitalists must interpret pyuria and bacteriuria in the clinical context of individual patients. Multiple society guidelines do not recommend the treatment of ASB, as current research does not support an association between pyuria, bacteriuria, and neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Quiz

An 88-year-old female with dementia presents to the emergency department accompanied by her daughter, who is concerned about a change in the patient’s urine color and odor as well as multiple falls in the past week. The patient cannot provide a history. The daughter denies her mother having had any recent concerns such as dysuria, abdominal pain, fatigue, fevers, or chills. Vital signs show a temperature of 37.0°C (98.6°F), heart rate of 88 beats per minute, blood pressure 120/60 mmHg, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, and O2 saturation 98% on room air. Workup included WBC of 8,000/μL and urinalysis with positive nitrite and LE, 12 WBC per HPF, and 0 squamous cells. What is the most appropriate next step?

A. Repeat the urinalysis

B. Neurologic exam and assessing for metabolic derangements on blood work

C. Collect urine culture and hold off on antibiotics until results are available

D. Collect urine culture and start trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for a five-day course

Correct option: B. This nonpregnant patient without clear genitourinary symptoms or upcoming urologic procedure does not require a urine culture to assess her falls. Given that there are no squamous cells on the urinalysis and she is not symptomatic, repeating a urinalysis (A) would not change her management. A urine culture (C) would also not change management as asymptomatic pyuria, with or without bacteriuria, does not require treatment (D) and puts the patient at risk for adverse events from antibiotics.

Additional Reading

- Advani SD, et al. Deconstructing the urinalysis: A novel approach to diagnostic and antimicrobial stewardship. Antimicrob Steward Healthc Epidemiol. 2021;1(1):e6. doi:10.1017/ash.2021.167.

- Reppas-Rindlisbacher C, Kandel C. Are antibiotics helpful for older adults with delirium and pyuria or bacteriuria? NEJM Evid. 2023;2(9):EVIDtt2300119. doi:10.1056/EVIDtt2300119.

Dr. Giordano

Dr. Turner

Dr. Shuman

Dr. Giordano is a hospitalist at Duke Regional Hospital and a medical instructor in the department of medicine at Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, N.C. Dr. Turner is an infectious disease specialist at Duke Infectious Diseases Clinic and an assistant professor in the division of infectious diseases at Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, N.C. Dr. Shuman is a hospitalist at Duke Regional Hospital and a medical instructor in the department of medicine at Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, N.C.

References

- Gupta K, et al. How testing drives treatment in asymptomatic patients: level of pyuria directly predicts probability of antimicrobial prescribing. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(3):614-621. doi:10.1093/cid/ciz861.

- Laguë A, et al. Investigation and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in older patients with delirium: a cross-sectional survey of Canadian physicians. CJEM. 2022;24(1):61-67. doi:10.1007/s43678-021-00148-1.

- Bilsen MP, et al. Current pyuria cutoffs promote inappropriate urinary tract infection diagnosis in older women. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76(12):2070-2076. doi:10.1093/cid/ciad099.

- Jacob MS, et al. Use of a midstream clean catch mobile application did not lower urine contamination rates in an ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(1):61-65. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2017.07.016.

- Cheng B, et al. Correlation of pyuria and bacteriuria in acute care. Am J Med. 2022p;135(9):e353-e358. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2022.04.022.

- Potts L, et al. A double-blind comparative study of norfloxacin versus placebo in hospitalised elderly patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1996;23(2):153-61. doi:10.1016/0167-4943(96)00715-7.

- Dasgupta M, et al. Treatment of asymptomatic UTI in older delirious medical in-patients: A prospective cohort study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;72:127-134. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2017.05.010.

- Joo P, et al. Effect of inpatient antibiotic treatment among older adults with delirium found with a positive urinalysis: a health record review. BMC Geriatrics. 2022;22(1). doi:10.1186/s12877-022-03549-8.

- Stall NM, et al. Antibiotics for delirium in older adults with pyuria or bacteriuria: A systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2024;72(8):2566-2578. doi:10.1111/jgs.18964.

- Fralick M. Antibiotics for delirium in older adults with no clear urinary tract infection (A-DONUT); Identifier: NCT06004739. ClinicalTrials.gov website. https://inclinicaltrials.com/infectious-disease/NCT06004739/details/. Accessed April 23, 2025.

- Memari M, et al. Things we do for no reason™: obtaining urine testing in older adults with delirium without signs or symptoms of urinary tract infection. J Hosp Med. 2021. doi:10.12788/jhm.3620.