A 68-year-old male with left hemiplegia resulting from a cerebrovascular accident, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and a left ureteral stone presents to the emergency department with diarrhea, dysuria, and urinary urgency.

A 68-year-old male with left hemiplegia resulting from a cerebrovascular accident, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and a left ureteral stone presents to the emergency department with diarrhea, dysuria, and urinary urgency.

Urinary frequency began three days before admission, and dysuria started two days prior. The urine exhibited a pink discoloration. These urinary symptoms were accompanied by abdominal and flank pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbances due to frequent bathroom trips. The diarrhea commenced one week earlier, without any associated melena or hematochezia, and was accompanied by rigors. The patient denies experiencing any nausea, vomiting, chest pain, or shortness of breath. Urinalysis revealed 3+ protein, a high level of leukocyte esterase with a white blood cell count exceeding 182, significant hemoglobin with a red blood cell count of 103, and numerous bacteria. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis identified a 4 mm left renal stone without perinephric stranding or inflammatory changes in the colon. In the emergency department, the patient presented with a systolic blood pressure of 86 mmHg, a respiratory rate of 15 breaths per minute, a pulse of 100 beats per minute, and a white blood cell count of 10.9. A one-liter fluid bolus was given, resulting in a systolic blood pressure recovery to 119 mmHg and a pulse of 97. Blood cultures and lactate levels were obtained, and ceftriaxone was initiated. The patient was transferred to the hospital medicine team, having met two of the four systemic inflammatory response syndrome, or SIRS, criteria for sepsis.

When analyzing this case, consider the following question: Is this patient benefiting from the standard-of-care sepsis bundle?

Definitions

The pursuit of certainty is ingrained in the medical profession, and diagnostic uncertainty is perceived as undesirable and uncomfortable.1 As contemporary medical practice is scrutinized through the lens of high-value care, this attitude of “chasing a diagnosis” has been highlighted as a potential risk for medical overuse, and its occurrence is categorized as overdiagnosis.1

Overdiagnosis is broadly understood as the labeling of a person with a disease or abnormal condition that would not have caused the person harm if left undiscovered.2 Although the diagnosis is accurate and the finding represents a true positive, individuals derive no clinical benefit from it, and it may expose them to physical, psychological, or financial harm.2-4 Examples include incidentalomas, solitary pulmonary nodules, thyroid nodules, subsegmental pulmonary embolisms, and other entities such as the sepsis diagnosis, based on systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria, as described in the clinical vignette. In this piece, we explore the complex interplay that surrounds overdiagnosis, including its drivers, triggers, and consequences. In addition, we explore risk mitigation strategies, highlight current challenges, and contextualize overdiagnosis in the inpatient setting.

A Model for Overdiagnosis

As an epistemological problem, the issue of overdiagnosis materializes from the convergence of unreliable information (inherent to our imperfect diagnostic means) and the need to identify and categorize disease early to improve outcomes. The tension between these two realities is further influenced by therapeutic interventions that expose patients to harm and provide varying degrees of clinical benefits.5

Although originating from this opposition, overdiagnosis is only significant in the right epidemiological environment. A rich reservoir of an undiagnosed subclinical disease is needed, consisting of low-grade instances of the disease that, in the absence of intentional search, would elude detection.2 In addition, a readily available diagnostic method with the capability of detecting these instances is needed, allowing the clinician to “tap” into this reservoir, usually prompted by standardized screening protocols or extensive diagnostic workups.2

This complex interplay results in the overdiagnosis conundrum, where efforts to decrease underdiagnosis of serious occult disease lead to an increase in the identification and potential treatment of subclinical and benign forms of the disease, which would have never been identified otherwise and would not have an impact on the patient’s clinical outcomes.

Drivers

With this model in mind, several drivers have been identified that increase the risk of overdiagnosis in a population. These include factors related to medical practice, patients, and the healthcare system, as well as technological advancements, economic interests, and cultural beliefs.6 These factors often work in tandem, leading to clinical practice shifts that expose a larger part of the population to unnecessary testing and treatment.

As many of these factors stem from forces that drive decision making in the medical field, the role of healthcare professionals in impacting the rate of overdiagnosis cannot be overstated.6 An intolerance towards uncertainty is often cited as a powerful motivator for diagnostic testing. Three potential factors underlying unnecessary testing include problem-based learning strategies in medical education that encourage a shotgun approach to diagnosis; perceived pressure exerted by patients to perform wider investigations; and fear of litigation.3

The contribution of industry interests to the growing rate of overdiagnosis has been extensively discussed in the literature.3,7,8 A recent example of this occurred in 2013 when an expert panel recommendation for a modification of the indications for statin medications increased the number of healthy people taking the medications by more than 13.5 million in the U.S. alone.9 When analyzing the panel, eight out of the 16 panelists had industry ties, including the chairman and two additional co-chairs.10 This pattern is not unusual, as research shows that 75% of members of panels responsible for defining the most common diseases in the U.S. have ties to industry that stood to benefit from expanded definitions.11 Additionally, the use of industry-issued direct-to-consumer marketing capitalizing on a patient’s fear of undiagnosed disease has also been highlighted as an important factor in the growing rate of unnecessary diagnostic procedures.3,7

Several systemic features also factor into the increasing rate of overdiagnosis. Fee-for-service reimbursement, for example, financially rewards medical practice that errs on the side of providing more care. Another notable case is supply-sensitive care, where higher capacity drives medical utilization and is bound to uncover an excess of abnormalities. Finally, underuse-focused healthcare-quality evaluations lead to physicians showing a disproportionate improvement in quality indicators aimed at insufficient use when compared to resource overuse.3

Impact of Overdiagnosis

The relevance behind mitigating the risk of overdiagnosis lies in its negative impact on patients, medical practice, healthcare institutions, and the environment.1,3,12,13 A conceptual map created by Korenstein et al. of the consequences of overuse can be used to describe the negative impact that overdiagnosis has on patients. This framework describes six distinct categories of harm: physical effects, psychological effects, treatment burden, social effects, financial strain, and overall dissatisfaction with health care.14

The negative impact that overdiagnosis has on the physical health of patients stems from the underlying risk posed by medical diagnostic methods and therapeutic interventions. As described by Coon et al., “a single test can give rise to a cascade of events, many of which have the potential to harm.”3 It is through that chain of events that a screening test, virtually harmless on its own, has the potential to impair quality of life and lead to increased morbidity and mortality caused by adverse effects and complications of unnecessary subsequent testing or treatment.1,12

These diagnostic and therapeutic efforts represent an important financial strain for both patients and the healthcare system. Unnecessary and wasteful care is estimated to constitute between 21% and 47% of all healthcare-related expenditure, a number that probably doesn’t fully represent the waste associated with overdiagnosis, as in many cases it is assumed to be necessary, regardless of its benefit to the patient.12,15

An often-overlooked consequence of overdiagnosis is the psychological harm associated with being labeled with a disease. This identification impacts the relationship between patients and themselves, their close relatives, and society as a whole, putting the patient at risk for stigmatization and further morbidity, and indirectly placing them at a disadvantage when applying for health benefits.2,12,16,17

The negative impact that overdiagnosis has on the environment is a matter of current discussion in the academic field, as the healthcare sector contributes 4.6% of greenhouse-gas emissions, and overtreatment (frequently secondary to overdiagnosis) contributes up to $101.2 billion (U.S.) in annual cost of medical waste.13,18

Mitigating the Risk

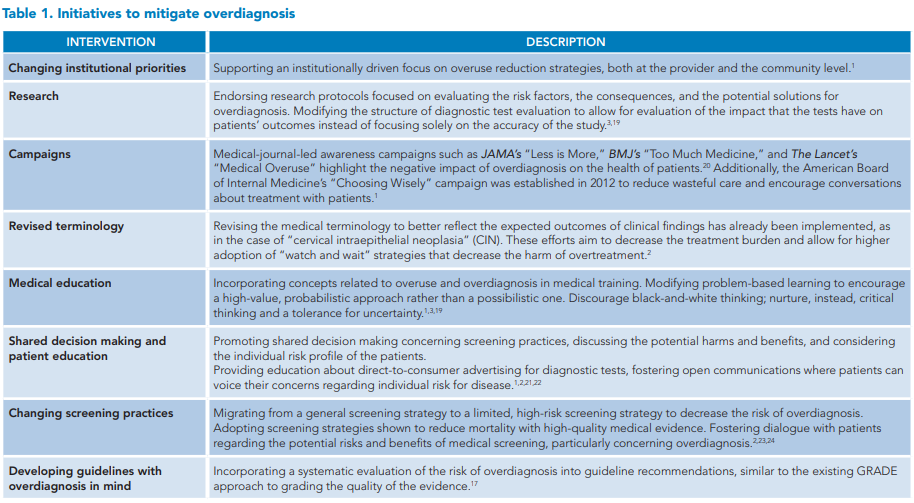

The growing body of clinical evidence showing the harm caused by overdiagnosis has sparked significant interest in developing initiatives that counteract the risk factors associated with its development. These include changes in institutional priorities, research focus, medical screening, and shared decision making, as well as awareness campaigns, modifications of the medical education curriculum, and the development of clinical guidelines that consider overdiagnosis (Table 1).

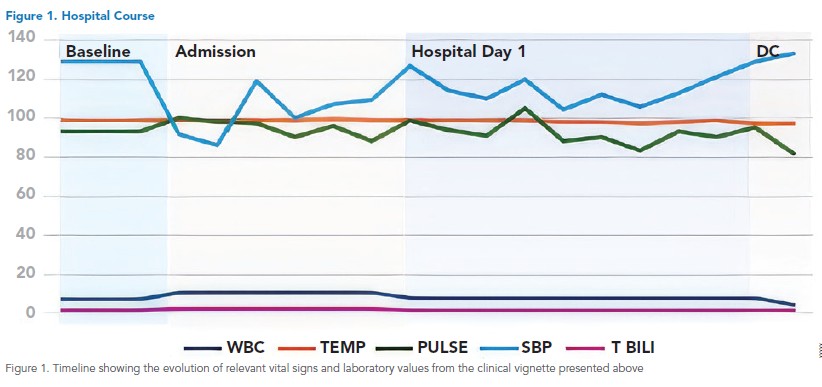

Looking back at the case vignette, the patient was admitted to the medical ward with a diagnosis of sepsis and continued on antibiotics and aggressive volume control. A close follow-up of the patient’s vitals and relevant laboratory values (Figure 1) showed an unusually quick resolution, which prompted the team to reconsider the initial diagnosis.

Sepsis Overdiagnosis: A Case Analysis

As the most expensive inpatient condition in the U.S., sepsis not only affects patients’ outcomes and well-being but also places a burden on institutional resources.25 Even with its diagnostic revision, sepsis remains a challenging entity to identify due to its complex clinical presentation, the wide spectrum of mimics, and the substantial increases in mortality associated with treatment delay.25–28 This milieu has led to institutional practices that favor prompt treatment initiation over diagnostic certainty, in the hope that by acting aggressively, patient outcomes can be improved.27,29 However, studies exploring the clinical impact of these “bundled sepsis care” practices reported increased rates of antibiotic use without significant reductions in sepsis mortality trends.27,30 This raised concerns about a growing rate of sepsis overdiagnosis, prompting several groups to examine their cohorts in this light. Interestingly, published studies vary considerably in their results, with overdiagnosis incidence estimates ranging from 8.5% to 43%.25,27,28,30 In addition to methodological concerns relating to the inherent limitations of retrospective studies, these varying results point to a significant problem in the study of overdiagnosis in clinical practice: its identification.

Challenge of Identifying Overdiagnosis

One of the biggest challenges surrounding the identification and characterization of overdiagnosis lies in its measurement. The traditional approach to identifying overdiagnosis relies on a careful analysis of clinical studies based on population screening programs, with multiple methods available to quantify its incidence.31 However, results vary widely depending on the methodology used, even when studying the same condition.2,4 In their state-of-the-art review, Senevirathna and colleagues explore the available methods for quantifying overdiagnosis, analyzing their limitations, and addressing the varying results obtained with each approach.4 Nonetheless, solving the problem of adequately measuring overdiagnosis does not address a bigger problem in its clinical applicability.

Overdiagnosis is, by definition, a retrospective diagnosis. It is the product of a decision taken in clinical uncertainty. It can only be properly named as such once the identified disease is proven to be harmless and the consequences of overtreatment have already occurred. Thus, while it remains a useful tool in identifying population trends, its current definition is of no clinical benefit for the individual patient. With this in mind, several authors have proposed modifying the formal concept of overdiagnosis for it to apply to the care of individual patients, with some even suggesting that a reconceptualization of our idea of disease is needed for this to be possible.16,32–34

The issue of overdiagnosis challenges our traditional conceptions of disease. By highlighting the inadequacy of diagnostic criteria and uncovering the existence of states that fit poorly into our traditionally dichotomic conception of health, overdiagnosis encourages doctors and patients to think differently about cases that fall within this borderline zone. When approaching this question, authors argue for the adoption of alternative accounts of disease, some labeling it a “vague concept” that does not have clear boundaries and thus allows for the classification of borderline cases that resist traditional labeling.7,16 In addition, such a definition underlines the relationship between our inherently flawed diagnostic criteria and the conceptions of disease, as well as our subjective accounts of harm, risk, and dysfunction used to characterize it.16

Conclusion

While overdiagnosis may be a phenomenon that neither physicians nor patients frequently consider, there is clearly potential for harm as a result. Due to the nature of our diagnostic model and our collective ethical imperative of beneficence towards our patients, physicians’ inherent need to be precise and exact can paradoxically lead to downstream effects that are undesirable. While it is of course difficult to identify overdiagnosis in real time and thus mitigate its risks to patients and our health care system, many well-known examples exist and can be reviewed with the hope of informing current and future practice. Likewise, although several strategies exist to mitigate the risk and harms of overdiagnosis, knowledge combined with practical approaches is favored.

Dr. Bayro-Jablonski

Dr. Iyer

Dr. Wardrop

Dr. Bayro-Jablonski is a first-year internal medicine resident at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio. Dr. Iyer is a hospitalist in internal medicine and a clinical professor at UCI Health in Orange, Calif. Dr. Wardrop is the chief medical officer and professor of medicine and pediatrics at Northeast Ohio Medical University Healthcare in Rootstown, Ohio, chair of the American Board of Internal Medicine’s board, and an American Board of Internal Medicine council member.

References

1. Kamzan AD, Ng E. When less is more: the role of overdiagnosis and overtreatment in patient safety. Adv Pediatr. 2021;68:21-35. doi: 10.1016/j. yapd.2021.05.013.

2. Dunn BK, et al. Cancer overdiagnosis: a challenge in the era of screening. J Natl Cancer Cent. 2022;2(4):235-242. doi: 10.1016/j.jncc.2022.08.005.

3. Coon ER, et al. Overdiagnosis: how our compulsion for diagnosis may be harming children. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):1013-23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1778.

4. Senevirathna P, et al. Data-driven overdiagnosis definitions: A scoping review. J Biomed Inform. 2023;147:104506. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2023.104506.

5. Jha S. Overdiagnosis and the information problem. Acad Radiol. 2015;22(8):947- 8. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2015.06.002.

6. Colbert L, et al. Medical students’ awareness of overdiagnosis and implications for preventing overdiagnosis. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24(1):256. doi: 10.1186/ s12909-024-05219-2.

7. Bandovas JP, et al. Broadening risk factor or disease definition as a driver for overdiagnosis: a narrative review. J Intern Med. 2022;291(4):426-37. doi: 10.1111/ joim.13465.

8. O’Keeffe M, et al. Journalists’ views on media coverage of medical tests and overdiagnosis: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(6):e043991. doi: 10.1136/ bmjopen-2020-043991.

9. Lenzer J. Half of panelists on controversial new cholesterol guideline have current or recent ties to drug manufacturers. BMJ. 2013;347:f6989. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6989.

10. Stone NJ, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25_suppl_2). doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a.

11. Moynihan RN, et al. Expanding disease definitions in guidelines and expert panel ties to industry: a cross-sectional study of common conditions in the United States. PLoS Med. 2013;10(8):e1001500. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001500.

12. Jenniskens K, et al. Overdiagnosis across medical disciplines: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e018448. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018448.

13. Ali KJ, et al. Diagnostic excellence in the context of climate change: a review. Am J Med. 2024;137(11):1035-41. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2024.06.010.

14. Korenstein D, et al. Development of a conceptual map of negative consequences for patients of overuse of medical tests and treatments. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1401. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3573

15. Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513. doi: 10.1001/ jama.2012.362.

16. Walker MJ, Rogers W. Defining disease in the context of overdiagnosis. Med Health Care Philos. 2017;20(2):269-80. doi: 10.1007/s11019-016-9748-8 .

17. Theriault G, Grad R. Preventing overdiagnosis and overuse: proposed guidance for guideline panels. BMJ Evid-Based Med. 2024;29:272-274. doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2023-112608.

18. Shrank WH, et al. Waste in the US health care system: estimated costs and potential for savings. JAMA. 2019;322(15):1501-1509. doi: 10.1001/ jama.2019.13978.

19. Novoa Jurado AJ. Ethical aspects of overdiagnosis: Between the utilitarianism and the ethics of responsibility. Aten Primaria. 2018;50(Suppl 2):13-19. [Article in Spanish]. doi: 10.1016/j. aprim.2017.01.009.

20. Bell K, et al. A novel methodological framework was described for detecting and quantifying overdiagnosis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2022;148:146-59. doi: 10.1016/j. jclinepi.2022.04.022.

21. Theriault G, et al. Expanding the measurement of overdiagnosis in the context of disease precursors and risk factors. BMJ Evid-Based Med. 2023;28(6):364-8. doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2022-112117.

22. Menkes DB, Hoeh NR. Doctor-patient relationship is essential to curtail overdiagnosis. BMJ. 2022;378:o1750. doi: 10.1136/ bmj.o1750.

23. Jatoi I. Mitigating cancer overdiagnosis. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2022;13(4):671-3. doi: 10.1007/s13193-022-01546-2.

24. Kühlein T, et al. Overdiagnosis and too much medicine in a world of crises. BMJ. 2023;382:1865. doi: 10.1136/bmj.p1865.

25. Pandey SR, et al. Factors and outcomes associated with under‐ and overdiagnosis of sepsis in the first hour of emergency department care. Acad Emerg Med. 2025;32(3):204-215. doi: 10.1111/ acem.15074.

26. Adelman MW, et al. The accuracy of infection diagnoses among patients meeting Sepsis-3 criteria in the emergency department. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;77(2):327. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciad240.

27. Rhee C, et al. Measuring diagnostic accuracy for infection in patients treated for sepsis: an important but challenging exercise. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76(12):2056-8. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciad105.

28. Hooper GA, et al. Concordance between initial presumptive and final adjudicated diagnoses of infection among patients meeting Sepsis-3 criteria in the emergency department. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76(12):2047-55. doi: 10.1093/cid/ ciaa101.

29. Rhee C, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America position paper: recommended revisions to the national severe sepsis and septic shock early management bundle (SEP-1) sepsis quality measure. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(4):541-52. doi: 10.1093/ cid/ciaa059.

30. Rhee C, et al. Association between implementation of the severe sepsis and septic shock early management bundle performance measure and outcomes in patients with suspected sepsis in US hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(12):e2138596. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.38596.

31. Hendrick RE, Monticciolo DL. USPSTF recommendations and overdiagnosis. J Breast Imaging. 2024;6(4):338-346. doi: 10.1093/jbi/wbae028.

32. Hofmann B. Getting personal on overdiagnosis: on defining overdiagnosis from the perspective of the individual person. J Eval Clin Pract. 2018;24(5):983-7. doi: 10.1111/jep.13005.

33. Newman-Toker DE. A unified conceptual model for diagnostic errors: underdiagnosis, overdiagnosis, and misdiagnosis. Diagnosis. 2014;1(1):43-8. doi: 10.1515/dx-2013-0027.

34. Carter SM, et al. A definition and ethical evaluation of overdiagnosis. J Med Ethics. 2016;42(11):705-14. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2015-102928