Case

Case

Emily is a 35-year-old woman with no substantial medical history who presents to the emergency department (ED) due to severe headaches that have worsened in recent weeks. She also experiences dizziness, difficulty concentrating, and disturbed sleep. After receiving medication for her headaches, she is advised to reduce stress both at home and work, with a recommendation to follow up with her primary care doctor. During this follow-up, the physician attributes her symptoms to anxiety and stress at home, discussing the possibility of prescribing a different headache medication along with an antidepressant without any further investigation. Not convinced, Emily declines the antidepressant. Her symptoms persist, affecting her ability to carry out daily activities, prompting her to consult a neurologist three weeks later. A scan ordered by the neurologist reveals a mass in the basal ganglia, and further tests confirm the presence of a benign brain tumor. The journey from her initial ED visit to the final diagnosis spans nearly three months, leading to challenges at work and home and significantly impacting her daily life.

Medical gaslighting occurs when healthcare providers downplay or dismiss a patient’s symptoms or concerns, causing them to question the validity of their experiences. This phenomenon can lead to delayed diagnoses, ineffective treatments, and increased distress for patients.1 It has become especially prominent in various patient populations, particularly women, racial minorities, and individuals with chronic health conditions. In hospitals, where patients frequently show acute symptoms, this problem can significantly impact care delivery. It can manifest in several ways, such as:

- Invalidation of symptoms: Clinicians may dismiss symptoms as being psychosomatic or exaggerated, leading patients to question the legitimacy of their own experiences.

- Denial of knowledge: Patients’ knowledge about their own bodies and conditions may be disregarded, with clinicians assuming a superior understanding without considering the patient’s perspective.

- Disbelief and dismissal: Patients’ reports of symptoms or adverse reactions may be met with skepticism or outright disbelief, often documented in medical records with language that suggests doubt, such as using quotes or judgmental terms.

- Attribution to psychological causes: Symptoms may be attributed to psychological factors without adequate investigation of potential physical causes, particularly in marginalized groups.

Key Diagnoses and Symptoms Prone to Medical Gaslighting

Hospitalists often encounter conditions and symptoms prone to medical gaslighting due to their complex and nonspecific presentations. These include:

- Autoimmune disorders: Diseases like lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis often present with vague symptoms like fatigue and joint pain, leading to delayed or missed diagnoses.

- Chronic pain syndromes: Fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome are frequently dismissed as psychological issues despite their recognized physiological underpinnings.

- Persistent fatigue or weakness: Women or minority groups presenting with vague yet debilitating symptoms like chronic fatigue, muscle weakness, or general malaise may be told they are “just stressed” or “depressed.”

- Unexplained neurological symptoms: Migraines, dysautonomia, and early multiple sclerosis can be mistakenly attributed to stress or anxiety, especially in younger patients.

- Cardiac conditions: Women presenting with atypical chest pain often have delays in the diagnosis of myocardial infarction.

- Rare diseases: Conditions like Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, long COVID-19 syndrome, chronic infections like Lyme disease, or mast cell activation syndrome are easily overlooked or dismissed.

These examples highlight the need for a comprehensive and unbiased approach to patient evaluation, emphasizing the importance of listening to patient concerns and avoiding premature diagnostic closure.

Application of the Data

As the gatekeepers of inpatient care, hospitalists play a crucial role in identifying gaslighting and addressing it promptly. This issue is especially significant for hospitalists in the acute care environment, where complex symptoms and high-stress conditions can occasionally result in premature diagnostic conclusions.

Given the emphasis on value-driven healthcare and the need to manage clinical care alongside costs and duration of hospitalization, there is frequently a tendency to expedite the discharge of patients. When a patient reports fatigue, pain, or other non-specific symptoms, they might be told that their issues are merely due to stress, anxiety, or even overreacting. These assumptions invalidate the patient’s experience and delay critical diagnostic processes, leading to potential harm.2 As frontline care practitioners, hospitalists must be aware of these dynamics and strive to avoid them through active listening, comprehensive assessments, and a willingness to explore all diagnostic possibilities.

Factors contributing to medical gaslighting can include unconscious biases, cognitive overload, and systemic pressures in hospital settings. Hospitalists often work under high pressure with limited time for each patient, and implicit biases related to gender, race, and socioeconomic status may impact decision making.3 Additionally, time constraints and workload demands may lead to rushed assessments, leaving patients feeling dismissed. Hospitalists must be equipped to combat these pressures and prioritize thorough patient evaluation to ensure accurate diagnoses and reduce the risk of gaslighting.

The effects of medical gaslighting on patients are significant, especially for those with chronic illnesses. When their symptoms are misunderstood or dismissed, it often leads to heightened frustration and disillusionment toward healthcare providers. Hospitalists, who typically encounter patients at their most vulnerable moments, must serve as empathetic advocates by ensuring that patients’ concerns are genuinely acknowledged and that they receive comprehensive care. By recognizing symptoms and practicing active listening, hospitalists can empower patients and help restore their confidence in the healthcare system.4

Hospitalists’ Role in Preventing Gaslighting

Hospitalists often face patient situations with unusual presentations or symptoms that are out of proportion to the examination. Below are practical strategies hospitalists can implement to mitigate gaslighting and improve patient outcomes:

- Active listening and patient validation: Hospitalists can effectively combat medical gaslighting by actively listening to their patients. This involves dedicating adequate time and focus to genuinely understanding their concerns and avoiding interruptions or hasty conclusions. Using simple yet impactful phrases such as “I understand you” or “Let’s take the time to explore what’s happening” can help make patients feel validated and supported. It’s crucial for hospitalists to prioritize ensuring that patients feel heard and respected during every interaction.

- Exploring symptoms holistically and asking open-ended questions: Hospitalists should take the time to fully explore symptoms and avoid jumping to conclusions based on limited information. Instead of immediately attributing symptoms to psychological causes, hospitalists should ask open-ended questions such as, “When did these symptoms start?” or “What factors seem to make your symptoms better or worse?” This approach allows for a comprehensive assessment and a more accurate diagnosis.

- Addressing unconscious biases and promoting equity in care: Implicit biases often unintentionally influence clinical decision-making. Hospitalists must engage in self-reflection and bias recognition training to better understand and address these unconscious biases. Regular cultural competency training is essential in reducing disparities in care and ensuring that all patients, regardless of gender, race, or socioeconomic status, receive equal attention and respect.

- Fostering patient-centered care: Hospitalists must focus on patient-centered care by viewing each individual holistically in every interaction. This involves evaluating physical symptoms while considering mental health, lifestyle choices, and the patient’s preferences when determining treatment options. By integrating patients’ viewpoints into decision-making, hospitalists can build trust and empower patients, reducing the risk of medical gaslighting.

- Collaborative and team-based care: Hospitalists should work with multidisciplinary teams, including specialists, social workers, and patient advocates, to offer holistic care for patients. This collaborative approach guarantees that patients receive a comprehensive assessment, decreasing the chance that their symptoms will be overlooked or downplayed.

- Advocating for systemic change: Hospitalists must advocate for policies and procedures that promote patient advocacy and address issues of gaslighting in hospital settings. This includes advocating for mandatory bias awareness training, empathy development programs, and creating patient advocacy teams. Hospitalists should also work with leadership to implement diagnostic protocols that ensure all patients receive comprehensive evaluations before attributing symptoms to psychological causes.

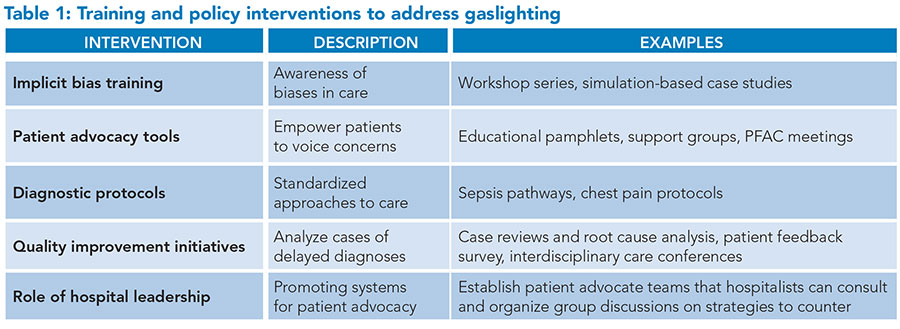

Hospitalists must also reject work conditions that lead to patient dissatisfaction with interactions.5 After a negative workup, hospitalists should communicate with the patient tactfully. They must adopt an empathetic tone and collaborate with the patient as a partner or coach when introducing the possibility that some aspects of a patient’s condition may stem from psychological or emotional health disturbances. Hospitals should implement mandatory bias awareness training to reduce gaslighting to help hospitalists recognize and address implicit biases.6 Empathy development programs can improve communication by fostering active listening and patient-centered care.7 Policies promoting diagnostic rigor should require thorough evaluations before symptoms are attributed to psychological causes. Establishing patient advocacy systems such as patient and family advisory councils, or PFACs, allows patients to voice concerns and seek second opinions, ensuring their voices are heard. Additionally, quality improvement initiatives that analyze cases of delayed diagnoses can identify trends, enabling targeted interventions to prevent future instances of dismissive care. These measures can enhance trust and improve patient outcomes. Table 1 summarizes additional interventions to address gaslighting.

Hospitalists must also reject work conditions that lead to patient dissatisfaction with interactions.5 After a negative workup, hospitalists should communicate with the patient tactfully. They must adopt an empathetic tone and collaborate with the patient as a partner or coach when introducing the possibility that some aspects of a patient’s condition may stem from psychological or emotional health disturbances. Hospitals should implement mandatory bias awareness training to reduce gaslighting to help hospitalists recognize and address implicit biases.6 Empathy development programs can improve communication by fostering active listening and patient-centered care.7 Policies promoting diagnostic rigor should require thorough evaluations before symptoms are attributed to psychological causes. Establishing patient advocacy systems such as patient and family advisory councils, or PFACs, allows patients to voice concerns and seek second opinions, ensuring their voices are heard. Additionally, quality improvement initiatives that analyze cases of delayed diagnoses can identify trends, enabling targeted interventions to prevent future instances of dismissive care. These measures can enhance trust and improve patient outcomes. Table 1 summarizes additional interventions to address gaslighting.

Back to the Case

This case emphasizes the need for active listening and diagnostic vigilance. Rather than prematurely attributing symptoms to anxiety, the physician should have empathized with Emily, validating her concerns and asking follow-up questions to fully understand her symptoms. A comprehensive assessment of her symptoms could have prompted earlier diagnostic testing, like an MRI or a referral to a neurologist. This delay in diagnosis not only heightened her risk of complications but also undermined her trust in healthcare. It illustrates the necessity of ruling out life-threatening conditions before assigning psychological causes.

Bottom Line

Medical gaslighting can represent a significant risk to patient safety, contributing to diagnostic errors and disparities in care. It undermines patient safety and trust, and hospitalists have a unique opportunity to lead in reforming this aspect of care. By prioritizing patient-centered practices, addressing implicit biases, and advocating for comprehensive diagnostic assessments, hospitalists can significantly reduce instances of gaslighting and improve patient outcomes. As frontline providers, hospitalists are uniquely positioned to recognize and address this issue through improved communication, structured diagnostic processes, and advocacy for equity. By fostering a culture of trust and thoroughness, hospitalists can help mitigate the impact of medical gaslighting and ensure high-quality, patient-centered care.

Dr Sood

Dr. Shane

Dr. Slonim

Dr. Sood is a hospitalist at Banner Gateway Medical Center in Gilbert, Ariz., affiliated with MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas. Dr. Shane is a program director at Thomas University in Thomasville, Ga., and adjunct faculty at Fordham University in New York. Dr. Slonim is a professor of medicine, pediatrics, health systems science, and interprofessional practice at Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine in Roanoke, Va.

References

- Ng IK, et al. Medical gaslighting: a new colloquialism. Am J Med. 2024;137(10):920-922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2024.06.022.

- Au L, et al. Long COVID and medical gaslighting: Dismissal, delayed diagnosis, and deferred treatment. SSM Qual Res Health. 2022;2:100167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmqr.2022.100167.

- Watson-Creed G. Gaslighting in academic medicine: where anti-Black racism lives. CMAJ. 2022;194(42):E1451-E1454. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.212145.

- Tennant K, et al. Active listening. 2023. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. PMID: 28723044.

- Sutker WL. The physician’s role in patient safety: What’s in it for me? Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2008;21(1):9-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2008.11928347.

- Vela MB, et al. Eliminating explicit and implicit biases in health care: evidence and research needs. Annu Rev Public Health. 2022;43:477-501. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-052620-103528.

- Moudatsou M, et al. The role of empathy in health and social care professionals. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8010026.

While I agree that hospitalists should be compassionate listeners and tactfully explain test results and differential diagnoses, I think that in today’s environment we must continue to not prolong hospital stays and costs for workups that could be accomplished as an outpatient. We should not dismiss or gaslight, but we must also work within the constraints of a payer system that doesn’t not provide for prolonged stay and extensive workup of chronic or non-life-threatening conditions. The hospital is for acute illness, and HM providers can and must be compassionate and practical at the same time. It is a difficult balance, and one that we as leaders should constantly try to support our HM providers in via training, backing of prudent decisions, and resources such as timely availability of outpatient evaluation and testing. I don’t believe anyone thinks this patient should have had an MRI during her hospital stay with no focal neurologic manifestations, and her insurance company (paying on the DRG) would likely agree. But with a compassionate HM provider, backed with primary care follow up and a timely investigation, this patient could have received the care they needed while maintaining some degree of practicality.